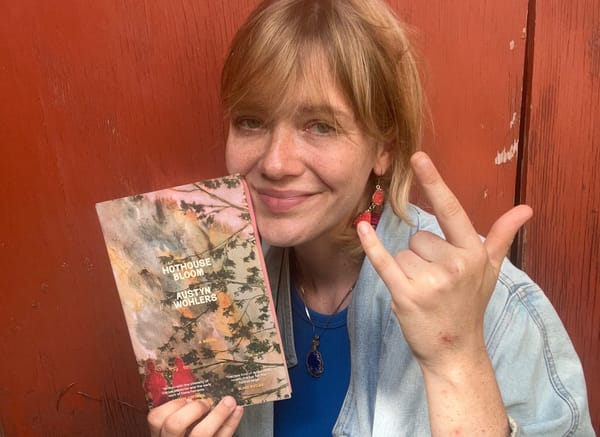

“A ticket out of the cookie factory’’: A Conversation with Hudson Valley Painter Taylor Morgan

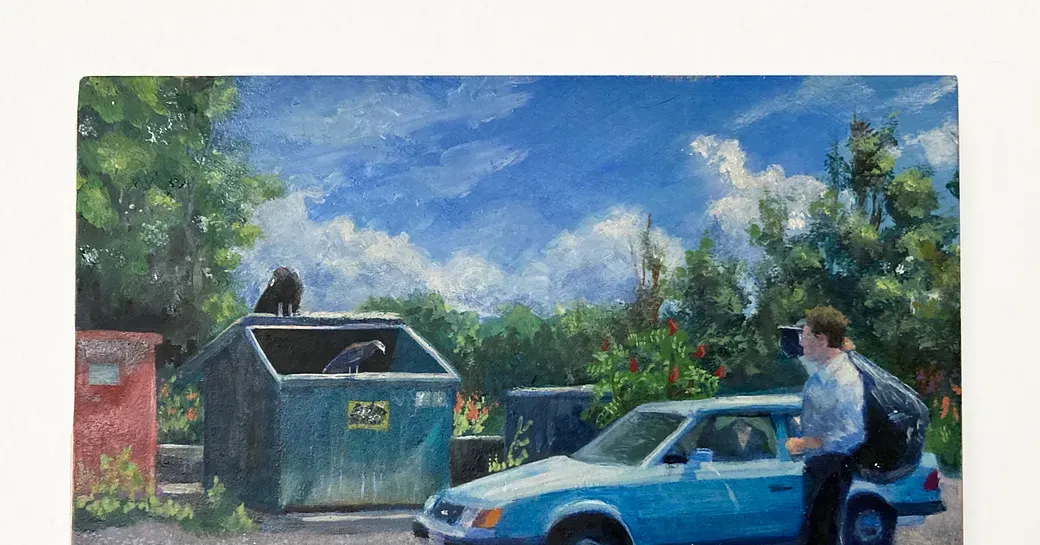

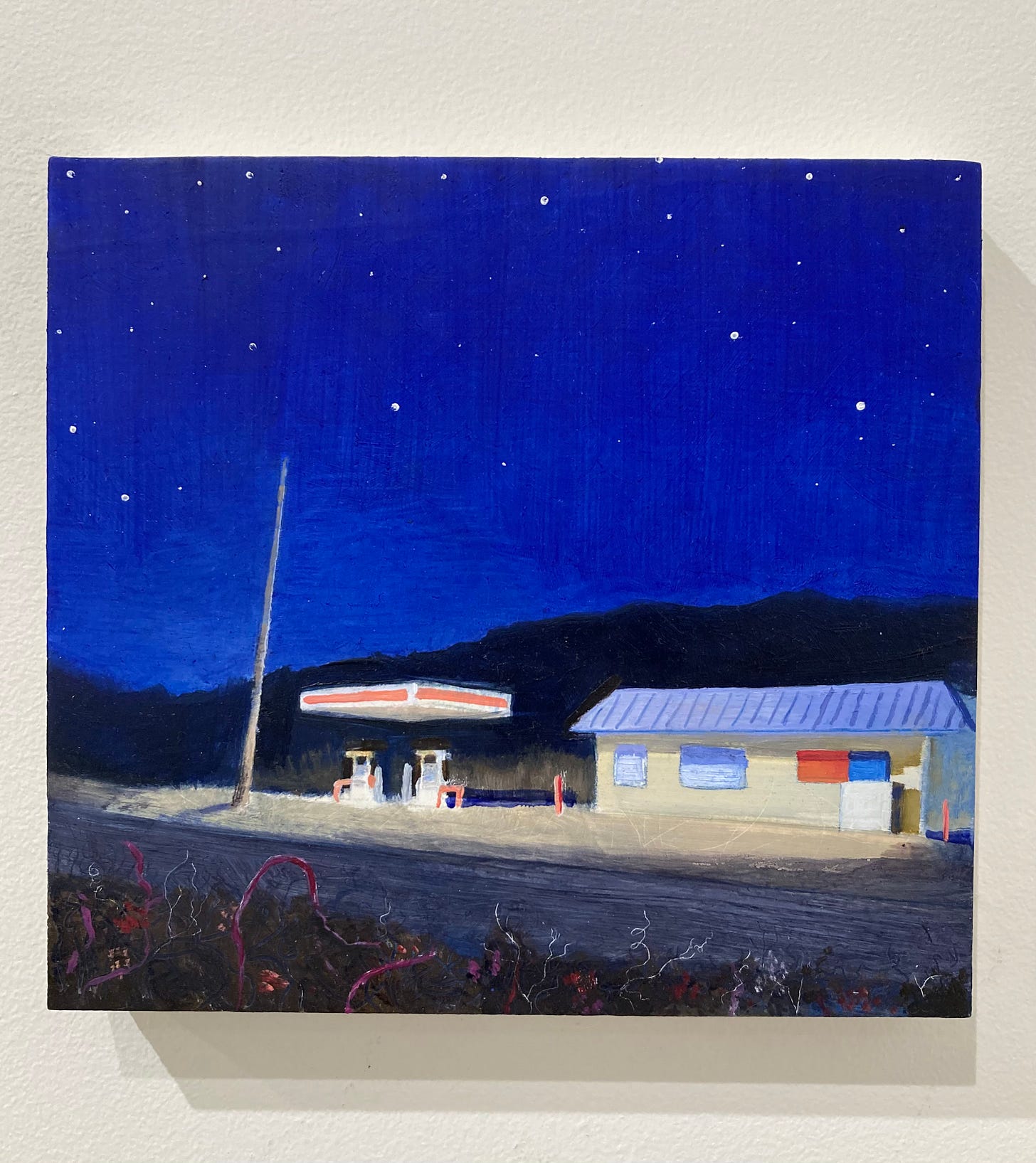

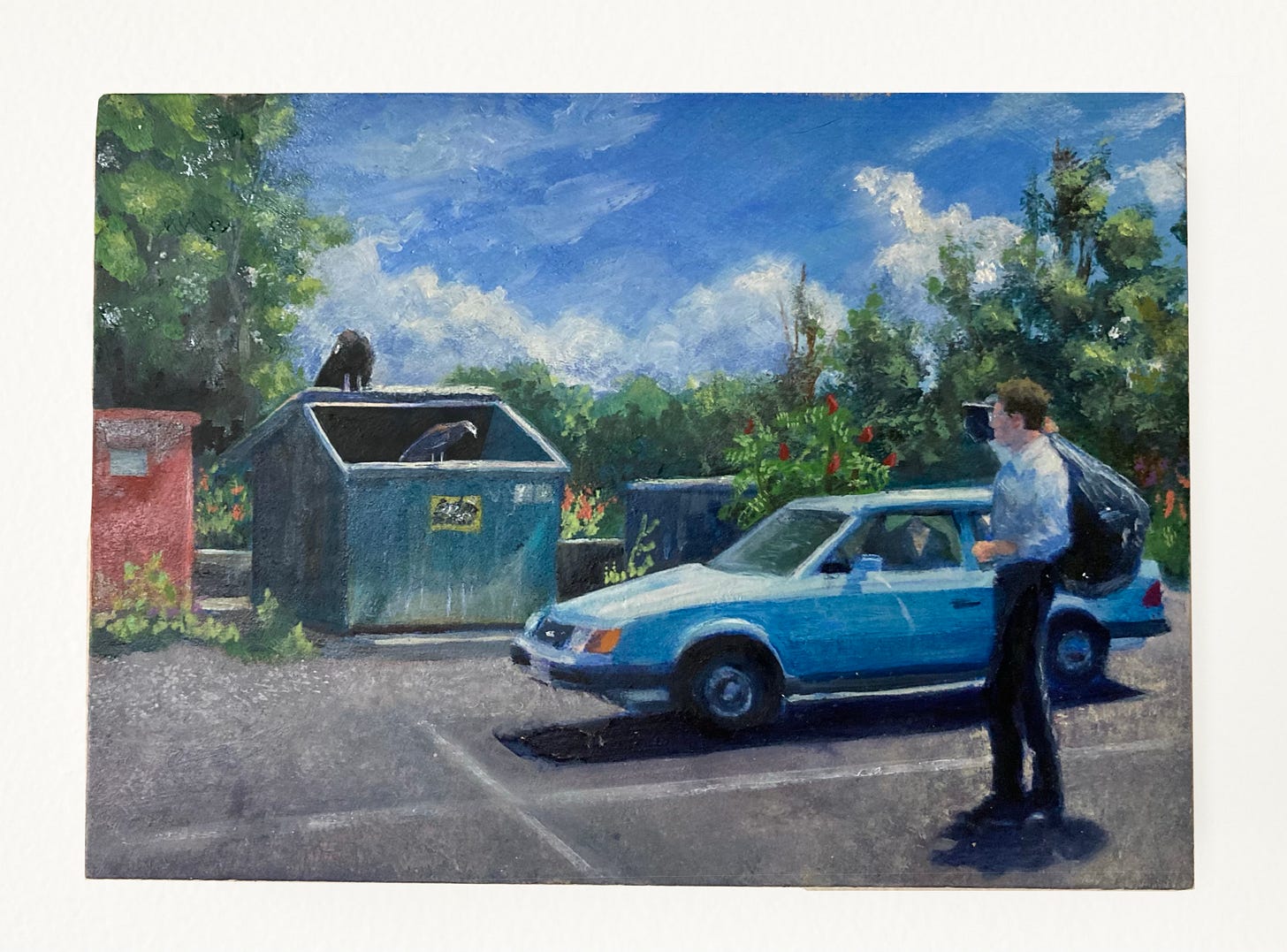

Taylor Morgan is a painter who works primarily in oil and acrylic on small panels. Her figurative work captures moments of conversation in which words are suspended in air: with the viewer pulled so closely into a moment as it unfolds, she expects, at any second, to feel the heavy breath of the speaking figure fall across her face. There is also a lonesome voyeurism in Taylor’s work. Just as the viewer discovers the world alongside the painters’ subjects, there are also moments where the viewer takes on a remote perspective and discovers that world from afar. This is the case for a piece titled Route 23, a panel showing an empty gas station illuminated by a fluorescent glow beneath a starry sky.

If you catch a train north from New York City, you can see Taylor’s paintings on the wall of The Aviary, a farm-to-table restaurant with a delectable menu in Kinderhook, New York. Taylor works as a server and studio assistant alongside Darren Waterston, the restaurant’s co-owner who is also a painter. The evening I met Taylor, she was acting as server and hostess, and I was playing the role of a sweaty and hungry tourist spending a weekend away from the city.

I first met Taylor Morgan as a voice over the telephone while trying to make a dinner reservation one weekend in Upstate New York. “773 - you’re a Chicago number,” she said. I asked how she knew. “I went to SAIC,” she replied.

Over the course of the meal, in the awkward moments we had together–walking to the table, conversing about the (delicious) food, within the strange dynamic of server and served–Taylor told me a little bit about she ended up in Chicago and then Kinderhook, and very graciously agreed to be interviewed for Working Artist.

At the height of the summer humidity, we speak over video, and Taylor tells me her story. She tells me how her love of painting began in a public education system that encouraged her to create. She tells me about Chicago and the lucky breaks that pushed her to continue painting. She tells me about the urge to continue painting in this sort of analog way–an approach that she loves deeply and has time and time again felt pushed to move away from. It’s an honest story, it’s the story of being young and a painter and trying to make it all come together.

ELIZABETH: Taylor, it is so wonderful to speak with you even over a Google Meets meeting. I like to start my interviews by asking the individual I am speaking with to introduce themselves in their own words. So, would you be able to tell me who you are in your own words?

TAYLOR: I've been painting for a long time. I went to specialized public middle and high schools in New York City where I focused on painting. This made studying art in college an obvious next step, there was little wavering about what I might do in college. When I was younger, I thought about being a costume designer or illustrator, but as I met more artists and art teachers, I realized that I was going to be a painter–the least practical career of them all.

I make small panels in a few different mediums, whatever I have around me at the time. They are portable. I work mostly in my living room at the moment. I really like working in my living room. I wish it was maybe a little bit bigger, but I like being able to just roll out of bed and paint and then make breakfast.

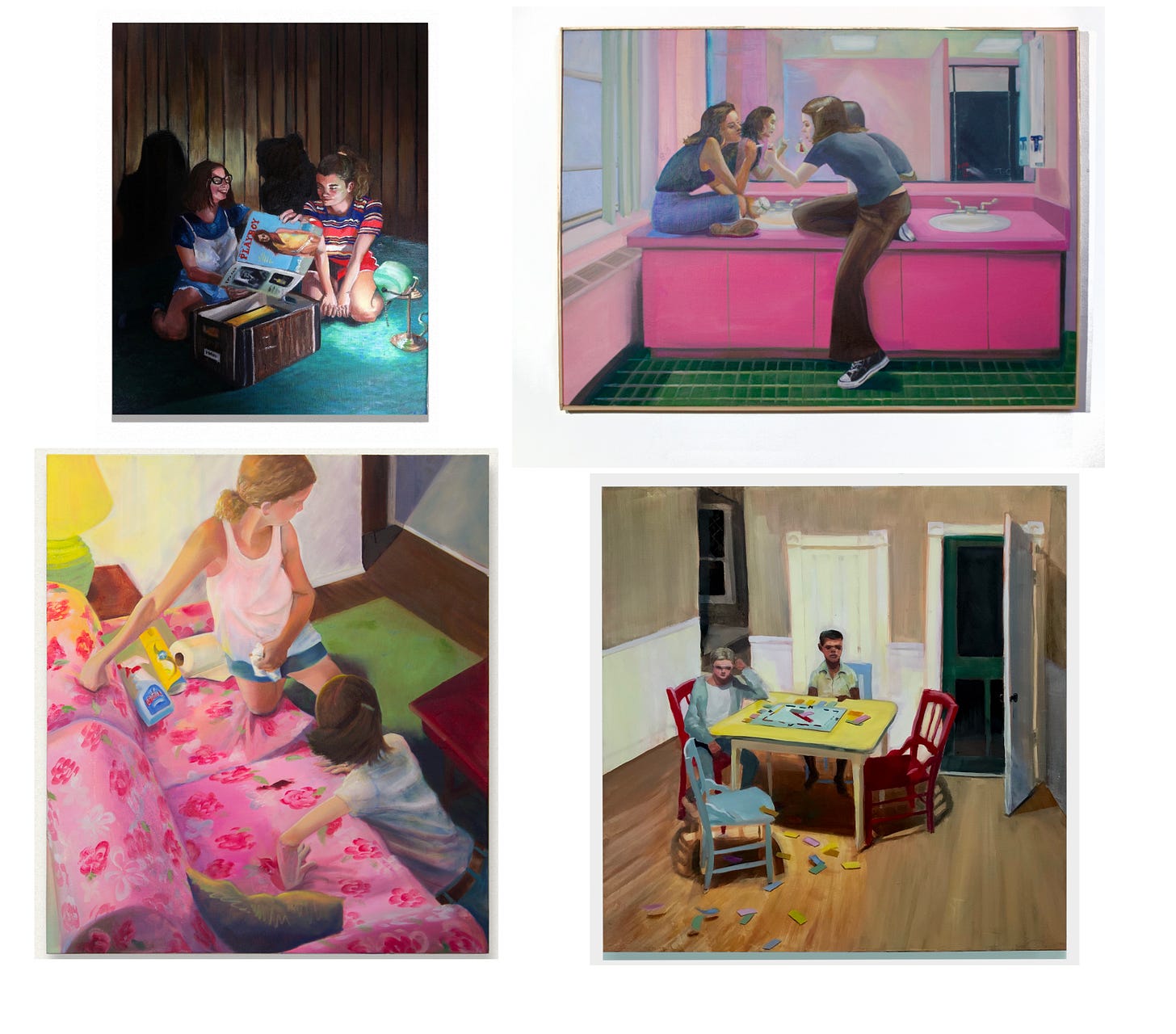

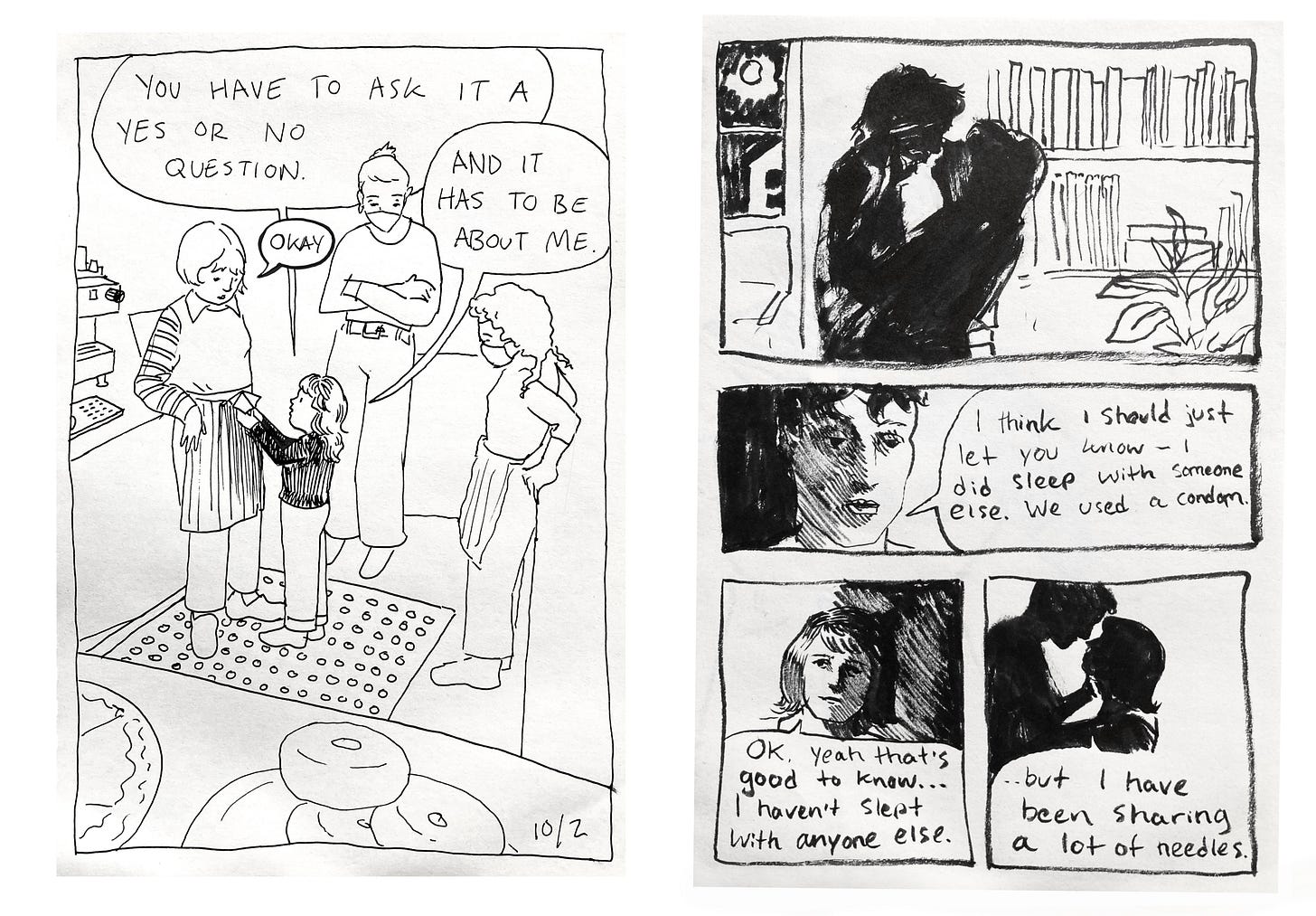

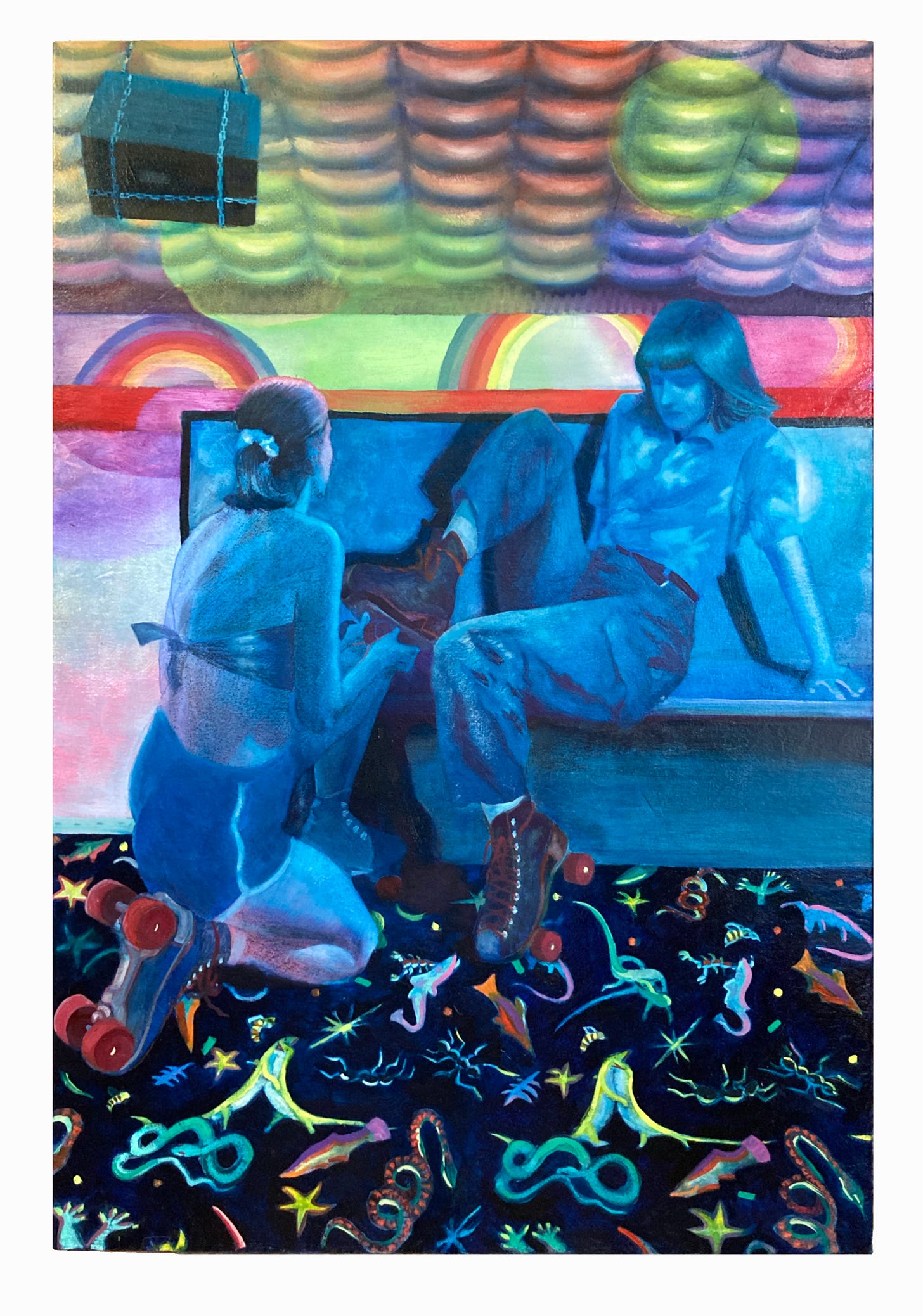

Most of my paintings are narrative-ish, like a scene painting. I grew up doing theater, and my family is in theater, so I feel that I have a strong interest in narrative painting and illustration. I am inspired particularly by the Golden and Silver age of illustration of the 19th and 20th centuries. I also do comics a little bit.

ELIZABETH: Something that really stands out to me that I want to start with is your mention of going to specialized middle and high schools for art. I know a lot of kids who went to these types of schools, and that really pushed the trajectory of their careers. I also know even more people who grew up in schools where the arts programming was defunded, and they just didn’t have access to the arts or artistic resources. I’m really interested in hearing more about the public resources that you had access to growing up and how they enabled you to get where you are today as an artist.

TAYLOR: I was definitely lucky growing up in New York City where there is access to strong public education. I went to schools where you would have to audition to gain admission, so I was doing that as a ten-year-old. I have a very supportive family, but the whole process was also very new to them. I remember at one audition, I was waiting to go in and everyone else was saying that you had to bring your own crayons, and of course, we didn’t bring our own crayons. My mom was freaking out, and she ran home to get me crayons for the audition. Of course, we didn’t actually need the crayons.

There are also great public resources in New York City that aren’t education, like museums that are free to New Yorkers. In high school, one of our assignments was to go to the Met and draw something in the museum. Our teacher would be like “quick, quick, go now, the Met closes at 5,” and we would all run across town because I went to LaGuardia which is on the opposite side of the Park from the Met.

We now have all these celebrity alums at LaGuardia from my time, like Timothy Chalamet. I don’t like to think about it. It makes me a little jealous.

I think they cut a little bit of the arts funding after I left because, I was told, there was a new principal and there was more emphasis on standardized testing. I spent so much time studying for those damn tests, and didn’t even apply to New York City or State colleges.

ELIZABETH: What year did they cut the funding, do you know?

TAYLOR: I think 2015. Though, at LaGuardia, I am not sure if it was funding cuts so much as a re-organizing of resources. I remember there was this article that came out about this really young dancer whose test scores weren’t very strong, but he was a phenomenal dancer, and he didn’t get into LaGuardia. He didn’t get into a school whose whole point was to be a space for him to hone his craft.

ELIZABETH: That’s so frustrating.

So, after LaGuardia, you went to SAIC, which is in my hometown of Chicago. I’m interested in learning more about why you chose SAIC and what the realities of moving to a new city were like for you.

TAYLOR: Cooper Union was my top choice school. I did not get in, which is okay. I remember procrastinating on the home test that I had to complete for Copper Union. I only applied to four schools: RISD, Pratt, SAIC, and Cooper Union. I did not get any scholarship for RISD, and money was a factor because I got the best scholarship for SAIC. It wasn’t amazing, though, there was still a lot of money weighing on me, as I am sure most people feel about student loans.

My parents took out Parent Plus loans, which I just recently found out about. The first year, we used Sallie Mae which was a huge mistake–don’t use Sallie Mae. Those have been paid off because the interest rate was just obscene.

I had been to Chicago when I was a kid, and the city just had warm tones associated with it in my mind. I wanted to get out of my hometown because I knew that I would get stuck living at home or something would happen where I just couldn’t escape my childhood. I think it was a good call to just leave.

I did like Chicago, but I feel like I was more scared than I thought I would be most of the time I was there because it was a new and different place. I lived in the dorm my first year. The dorms were in Downtown Chicago, which is such a random place: there is no community, no neighborhood. My first year was the school’s 150th anniversary, and I liked that they spent the year putting together community-based activities, but other than that, it was just not the school for me.

I think SAIC is super concept-oriented. We were always being asked “why are you making?” For an 18-year-old, that was a new question. Having an answer is not a bad idea, but I got really mixed up–scrambled, I think is the right word–because I started thinking that my art wasn’t useful. My art isn’t boundary breaking, it’s kind of retro. What I am doing is painting narrative scenes. It’s a little old fashioned, and SAIC is super modern. I know people who went in as painters and are now doing 3-D animation and illustration for The New York Times.

I didn’t have much interest in learning new technology. Ironically, illustrators of today are worried that AI might take over their job. Maybe I dodged a bullet by not going into illustration. What I really wanted to do was learn technique and skill building. That was less prioritized at SAIC.

ELIZABETH: I am really interested in what you are saying about the progression of illustration, because hand-drawn illustration was a huge part of the books of my childhood, and it is an art form I hold very dearly to my heart. I don’t know if “strange” is the right word, but it is strange to see less and less hand-drawn illustration in the world, and it’s wonderful to know people are still creating in this way. What drove you to continue painting and hand-drawn illustration, especially as so many people around you were going into digital spaces where there was a clearer, more comprehensive career path chiseled out before them?

TAYLOR:

“I think that the most interesting thing about so many paintings and illustrations is when you are able to get close and see little mistakes or little bits of cat hairs. All these happy accidents, and happy accidents aren’t the same in digital art. It’s a combination of appreciating the hand, and also laziness.”

I felt that I already had the building blocks of skill for oil painting. During Covid, I got an iPad and an Apple Pencil. I was home and had some stimulus money, and I got ProCreate–and I just couldn’t get into it. I was so used to holding a paintbrush and working on paper. There is something so special about looking at a book that is clearly hand-drawn or a comic where the lettering is hand-written. I think people will always want that.

ELIZABETH: One thing I love about Chicago is that I think of it as a place that really fosters a community around a DIY ethos of creating your own art and sharing that art. I also associate it with so many phenomenal imagists, like it truly feels like a hub for comics. Anyways, you go to SAIC and you graduate? What happens next?

TAYLOR: Well, I had a lucky break. I was in an advanced studio class, which is the only way to get your own studio at SAIC, and this guy who I shared a studio with told me that he was applying for a residency. I’d never heard of the residency, and I learned that you had to apply through SAIC, and SAIC would nominate you for the residency, and you would also need a letter of recommendation from a member of the SAIC staff.

I ended up getting into the program, which was the Yale Norfolk Artist Residency. They only take about 24 students from different art schools between their junior and senior year. You get 12 credits which go back to your degree which was huge because 12 credits cost so much to accrue.

It was a great experience. I love residencies. I loved being in this little town in Connecticut with weird moths and bugs, and I don’t even like bugs. I would work out of this musty old barn, which felt so different from SAIC which is so clean and corporate-feeling. I really began thinking, “oh, great, this is working out.”

I got my 12 credits, and I made the Dean’s list for SAIC. Those 12 credits from the residency were really the only reason I graduated in time because SAIC makes it so hard to get all the credits you need to graduate.

ELIZABETH: Schools seem to love making it hard to get enough credits to graduate.

TAYLOR: I remember my roommate was working at the Chicago Diner and she didn’t graduate on time and was struggling. I had been doing work-study. I was an usher for the visiting artists program all throughout school. My senior year, I worked at the Roger Brown Study Collection which was kind of a dream job.

The Collection is basically a little house full of knick-knacks and 20th century ephemera. I was cataloging and scanning photos. It was funny because it was such a good job, but if it weren’t for work study, I wouldn’t be qualified at all to be there because you need a master’s degree in museum studies. Everyone loved working there and then it was like, “good luck getting back here once you graduate.”

There was something else that is a huge part of my story, especially during the period of college. I also think it was very of the zeitgeist at the time which was around 2015-2019, and so many people were doing it. I dabbled in Seeking Arrangements–dabbling which really kind of worked for me.

I think a lot of people had bad experiences with the website. I also had some meh experiences with the website, but I was so freaked out about money.

“I couldn’t focus on school because I was obsessed with the idea of paying off loans. In my day-to-day life, I was okay, but the long-term realities of debt really freaked me out. I figured out that I could be on food stamps, and I was also doing Seeking Arrangements which enabled me to buy a new phone and pay off some of my Sallie Mae debt and have extra cash that I stored in a sock.”

I did escort work for 6-9 months and then my boyfriend at the time was not into it anymore, and I stopped. I think the narrative of doing escort work is so far removed from, at least, my experience of being raised as a “good girl.” My parents never in a million years thought I’d decide to do something like that, it just seems so crazy. It’s a sensitive subject but it’s a big part of my memory of college.

I felt a little frustrated because my mom was stressing me out about money. I ended up telling my parents years later and it really upset them, but we’ve moved on from that.

I feel like this belongs in this story, but I’m not sure how to tell it.

ELIZABETH: Thank you so much for sharing all of this. I know that escort work has been a key part of financial stability for many people I went to school with, but we so rarely talk about it. I really appreciate you sharing your experience.

To go back to your timeline–you get this phenomenal fellowship and then what happens?

TAYLOR: I graduated and then I moved with my boyfriend to an apartment in Albany Park, Chicago. The apartment was giant and falling apart. We were both painters, and I got a job at an art school called the One River School and was basically an after-school camp type of thing. It was cute, and I could bike to work.

Before that, I had tried working at a different art school that mostly did kid’s birthday parties. Most of the parties were “Jackson Pollock” themed, and the kids stomped around a canvas with acrylic paint barefoot. We had to wash their feet with hand wipes, and I remember thinking this is more degrading than any sex work I’ve ever done and I’m doing it in my field, art.

Right before Covid, my partner at the time and I put on a two person show featuring myself and another artist. I’d heard that because Chicago is a more affordable city, there are a lot of artists run spaces and galleries. Putting together that show felt like a big milestone. We didn’t sell anything, but the opening was really fun. We put a lot of effort into an installation in the gallery along with the paintings on the wall, and we painted the floor to make it all feel like a playroom.

The morning after that opening, I went to the Vermont Studio Center, another residency. I did have to pay for it, because I didn’t get a full ride, but I got some sort of scholarship. While I was there, Covid hit–so that was March of 2020. I was back and forth from Chicago, and then I broke up with my partner and moved in with my parents.

In New York, I got a job working at a bakery which is a cookie factory that makes custom portrait cookies. It was just barely starting when I got there, and my whole job was mixing icing colors, these really specific colors, which was kind of cool. It was very in my field, very color theory focused, and I felt good having a skill, but I was not making very much money.

I was really burnt out. I wasn’t making my own work at all. Everyone at the cookie factory was really talented and had just graduated from Pratt or SVA, and they were all sitting there hunched over these cookies.

And then I ended up re-connecting with my godmother who had moved to Hudson. She told me that her best friend, Darren, needed help with a mural upstate. Knowing I had some upstate mural job was such a relief because it meant I had a ticket out of the cookie factory. It was like I was let out of jail, and everyone was like “wow you’re doing murals in the Hudson Valley, wow you’re so lucky.”

I was very close to signing a lease with five roommates in Bed Stuy who all seemed really nice, but my room would have been overlooking trash cans on the street. Instead, I ended up with the big-windowed apartment upstate in the middle of nowhere.

And that catches us up pretty much to today.

ELIZABETH: Can you walk me through what you are doing in the Hudson Valley now?

TAYLOR: I work at a restaurant and am a studio assistant for Darren, who is a working painter. Darren found early success as a painter fresh out of school and he has been painting his whole life. He opened the restaurant I now work at, and we will sometimes work together for four hours in the studio and then five hours in the restaurant.

There are a lot of artists up here, and I was talking to one who was working behind the bar of the restaurant about her studio practice. I asked her how much time she devotes to her studio, and she told me something along the line of “ten hours a week.”

“Something clicked a couple of weeks ago. I realized I wasn’t caring enough about making my own work, I was putting everything ahead of it, and that was depressing because painting is what I love to do. Then, I spiral and think that if I really love painting, why am I not doing it right now, and I remember this warning we used to get in school which is that ‘no one is going to pay you to make your art.’”

But for me, painting has led to just enough, that I decided to develop a structure around it. I am doing seven hours a week of painting, which is really doable–it can be an hour a day. And I am trying to make a body of work, finding themes that really excite me.

There’s a gallery upstairs from the restaurant, and I’ve been in a couple of shows there. I’ve sold two paintings just off the wall of the restaurant. This is all very encouraging. I think my biggest issue is committing to the time in the studio/living room.

ELIZABETH: In a world where it is just so hard sometimes to find the time and resources and energy and appreciation to continue to create, why do you do it?

TAYLOR: I think creating feels good. I think it’s an innate human desire.

I also like the idea of making art that people want. It feels good making work that can go in someone’s home. Having art in a home is really important and wanted. People want art so badly in their home, there is a market for the Ikea or Walmart-type Audrey Hepburn poster that is pretending to be a painting.

I think it is a worthwhile pursuit to create art that people can afford. It’s not the reason to create, but it’s a factor. The whole idea of selling your work is so taboo in art school, we don’t talk about that. We talk about the noble and ambitious pursuit of art in the name of the greater good.

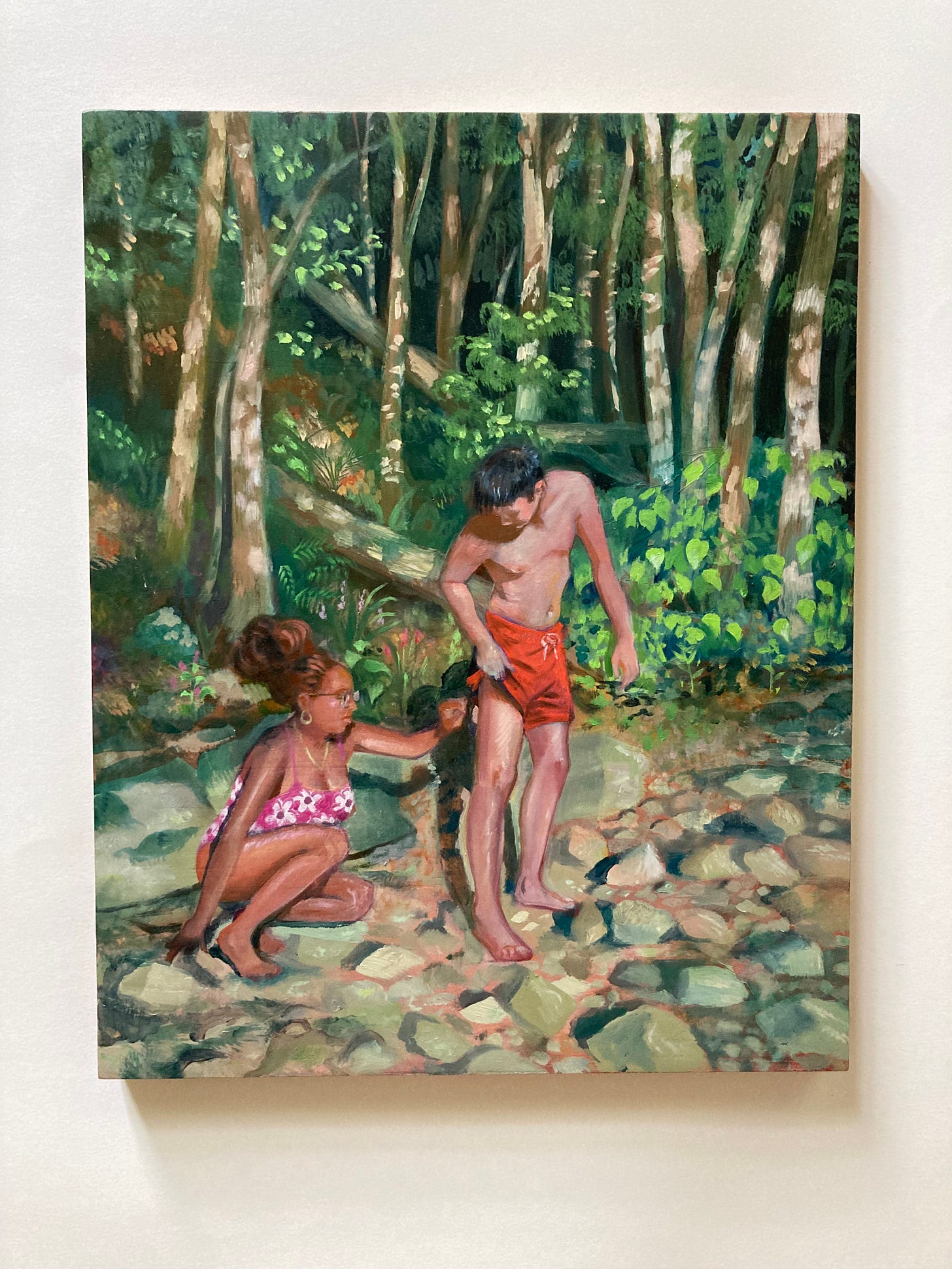

Taylor Morgan is a painter, illustrator, comic artist, barista, waitress, graphic designer, pet sitter, art teacher, studio assistant, and gallery attendant currently living and working in the Hudson Valley, originally from Brooklyn NY. Her work is mostly figurative and narrative driven, often focusing on themes from young adulthood, like friendship, anxiety and make-believe. She received her BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019. Residencies include the Yale Summer School of Music and Art in Norfolk CT in 2018, and the Vermont Studio Center in 2020/22. Recent group shows include, “Freaky Flowers” in 2023 and “In The Pale Moonlight” 2024 at September Gallery in Kinderhook NY.